本站将于近期进行系统升级及测试,您目前浏览的网站为旧版备份,因此可能会有部分显示和功能错误,为此带来的不便深表歉意。

阿尔茨海默症

| 阿尔茨海默症 | |

|---|---|

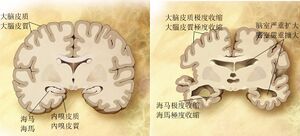

比较正常(左)和阿尔茨海默病(右)患者的脑部。 | |

| 同义词 | 老年痴呆症 |

| 症状 | 短期记忆丧失、语言障碍、定向障碍、情绪不稳 |

| 常见始发于 | 大于65岁[1] |

| 病程 | 慢性[2] |

| 肇因 | 了解有限 |

| 风险因子 | 遗传、头部外伤、忧郁症、高血压 |

| 诊断方法 | 排除其他可能原因后基于症状和认知测试诊断 |

| 相似疾病或共病 | [[正常老化[3]]] |

| 药物 | 乙酰胆碱抑制剂 NMDA受体拮抗剂(稍有帮助) |

| 预后 | 余命3至9年[4] |

| 患病率 | 2980万人(2015) |

| 死亡数 | 190万人(2015) |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 医学专科 | 神经内科 |

阿兹海默症(Alzheimer's Disease,简称 AD)或称脑退化症。旧称为Senile Dementia of the Alzheimer Type,缩写:SDAT}} 、奥茨海默症、老人失智症;俗称早老性痴呆、老人痴呆(但医界不建议使用此名称模板:备注)。阿兹海默症占了失智症中六到七成的成因[3][5],是一种发病进程缓慢、随着时间不断恶化的持续性神经功能障碍[5]。最常见的早期症状,是难以记住最近发生的事情[3],早期症状还应该增加行为或性格的改变,「轻微行为能力受损」(Mild Behavioral Impairment, MBI)[6],对平日最喜欢的活动失去兴趣、对人物冷感、对日常作息焦虑、无法控制冲动、多侵略性、挑战社会规范、对食物失去兴趣、事事疑心,突然经常动怒爆粗话。随着疾病的发展,症状可能会包含:谵妄、易怒、具攻击性、无法正常言语、容易迷路、情绪不稳定、丧失生存动力、丧失长期记忆、难以自理和行为异常等[3][5][7][8]。当患者的状况变差时,往往会因此脱离家庭和社会关系[3][7][8],并逐渐丧失身体机能,最终导致死亡[9]。虽然疾病的进程因人而异,很难预测患者的预后,但一般而言,确定诊断后的平均余命是三到九年[4],确诊之后存活超过十四年的病患少于3%[10]。

阿兹海默氏症的真正成因至今仍然不明[3]。目前将阿兹海默氏症视为一种神经退化的疾病[3],并认为有将近七成的危险因子与遗传相关[11];其他的相关危险因子有:头部外伤、忧郁症或高血压的病史[3]。疾病的进程与大脑中纤维状类淀粉蛋白质斑块沉积(Senile plaques)和涛蛋白(Tau protein[12])相关[11]。要确切地诊断阿兹海默氏症,需要根据病人病史、行为评估、认知测验(Cognitive tests)的结果、脑部影像检查和血液采检,亦可能接着做神经影像检查辅助诊断[13][14],以排除其他类似的认知障碍[15]。初期症状常被误认为是正常的老化状况[3],或是压力的一种表现[7][16],因而常耗时三到六年才确诊[17]。在无法排除其他可治愈原因时,有极少情况下,脑部切片可能对确诊有帮助[11]。认知保留研究(Cognitive_reserve)、运动、避免肥胖等,都有助于减少罹患阿兹海默氏症的风险[11][18]。目前并没有特定药物或营养补充品,有实证证明对疾病治疗有效[19]。

目前并没有可以阻停止或逆转病程的治疗,只有少数可能可以暂时(缓解)改善症状的方法[5]。截至2012年为止,已有超过1000个临床试验研究如何治疗阿兹海默症,然而这些研究是否能找到有效的治疗方法仍是未知数[20]。疾病会使患者会越来越需要他人的照护,这对照护者是一大负担;这样的照护压力涵括了社会层面、精神层面、生理层面和经济因素[21]。不同的运动计划,无论时间长度与每周运动频率,都能改善病人的居家生活表现功能,也对于改善预后有相当帮助[22]。由失智症状引起(造成)的行为异常和思觉失调,常以抗精神病药治疗,惟其效益不高且可能增加死亡率,因此并不特别建议使用[23][24]。

阿兹海默氏症最早于1906年,由德国精神病学家和病理学家爱罗斯·阿兹海默首次发现,因此而得名[25];主要分为家族性阿兹海默氏症与阿兹海默老年痴呆症两种,其中又以后者较常见[26]。阿兹海默氏症好发于65岁以上的老年人(约有6%发生率[3]),但有4%~5%的患者会在65岁之前就发病,属于早发性阿兹海默氏症(Early-onset Alzheimer's disease}[27]。在2010年,全球有将近2100万到3500万名阿兹海默氏症患者[5][4];而归因于阿兹海默氏症相关的死亡案例,大约有48.6万例[28]。在已开发国家中,阿兹海默氏症是相当耗费社会财政补助的疾病之一[29][30]。

简介[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

阿兹海默症是一组病因未明的原发性退行性脑变性疾病。多起病于老年期,潜隐起病,病程缓慢且不可逆,临床上以智能损害为主。病理改变主要为皮质弥漫性萎缩,沟回增宽,脑室扩大,神经元大量减少,并可见老年斑(SP),神经原纤维结(NFT)等病变,胆碱乙酰化酶及乙酰胆碱含量显着减少。起病在65岁以前者旧称老年病前期痴呆,或早老性痴呆,多有同病家族史,病情发展较快,颞叶及顶叶病变较显着,常有失语和失用。

诊断[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

阿兹海默症的初步诊断通常是由病患的临床病史、亲人的附带病史和临床医师观察到的神经学及神经心理学上的特征,经除外诊断获得[31][32],高阶医学影像技术如计算机断层扫瞄、核磁共振成像、单光子计算机断层摄影和正子计算机断层摄影可以用来排除其他大脑病变或失智症亚型[33]。更重要的是,医学影像也可以预测从轻微认知失调到阿兹海默症的转变[34]。

神经心理学评估(包括记忆测试)可以进一步鉴别疾病状态[7]。医学组织已经为临床执业医师建立诊断标准以简化及标准化诊断程序,若是可以取得脑组织,则可以经由高准确度的组织学免疫染色法检验进一步确认诊断[35]。

阿兹海默症的诊断先检查病史、进行神经检查及简短的智能测验。基本检查有神经心理测试、血液常规、生化检查(肝肾功能)、维他命B12浓度、甲状腺功能、梅毒血清检查及脑部计算机断层或磁振造影等,特殊情况亦有其他检查类型[36]。有失去记忆导致忧虑的症状,就可能罹患了阿兹海默症,但必须经过医师的智能测验及脑部断层扫描才能确定,以下是作为指标的智能量表。

| 阶段 | 智能测验说明 | 症状说明 | 平均期间 | 退化程度 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 一 | (MMSE:29-30) | 正常 | - | 成人 |

| 二 | (MMSE:29) | 正常年龄之健忘,与年龄有关之记忆障碍(忘记东西放置的地方及某些字,减少注意力) | - | 成人 |

| 三 | 轻度神经认知功能障碍(MMSE:25) | 降低从事复杂工作之能力及社会功能(例如:完成一件报告) | - | 年轻之成人 |

| 四 | 轻度阿兹海默氏失智症(MMSE:20) | 计算能力下降(100-7, 40-4),无法从事复杂活动(个人理财、料理三餐、上市场),注意力、计算及记忆障碍(近期为主) | 2年 | 8岁-青少年 |

| 五 | 中度阿兹海默氏失智症(MMSE:14) | 计算能力明显下降(20-2),失去选择适当衣服及日常活动之能力,走路缓慢、退缩、容易流泪、妄想、躁动不安 | 1.5年 | 5-7岁 |

| 六 | 中重度阿兹海默氏失智症(MMSE:5) | 无法念10-9-8-7……,需他人协助穿衣、洗澡及上厕所,大小便失禁,躁动不安,降低语言能力 | 2.5年 | 5-7岁 |

| 七 | 重度阿兹海默氏失智症(MMSE:0) | 需依赖他人持续照顾,除叫喊外无语言能力、无法行走,行为问题减少,增加褥疮、肺炎及四肢挛缩之可能性 | MMSE从23(轻度)→0约6年,每年约降3-4分,MMSE到0后可平均再活2-3年 | 4周-15个月 |

历史[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

德国精神病学家爱罗斯·阿兹海默于1907年[37]最初报告了这一病症,并由此得名阿兹海默症。

症状[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

阿兹海默症的病程根据认知能力和身体机能的恶化程度分成四个时期。

失智症前期[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

最初的症状常被误认为是老化或是压力[7],但是若进行详细的神经心理学检查(Neuropsychological test)可能可以发现轻微的认知困难,甚至能在确诊为阿兹海默症的八年前就可发现[38]。这些早期症状可以影响大部分复杂的日常生活活动[39],最明显的缺陷是失忆,主要是难以记住最近发生的事和无法吸收新信息[38][40],其他症状包括出现在注意力的管控、计划事情、弹性、和抽象化的微小问题,或是语义记忆障碍[38]。冷漠也是此时期会出现的症状之一,并且是整个病程中一直持续的神经精神病学(Neuropsychiatry)症状[41]。阿兹海默症的临床前期也被称为轻微认知障碍(Mild cognitive impairment)[40],然而这一名词是否即是阿兹海默症的另一个诊断期或是可以作为鉴别阿兹海默症的第一步仍旧有争议[40][42]。

早期症状[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

在阿尔茨海默病患身上的学习与记忆障碍会愈见明显最后使医师能确认诊断,在某些病患中,语言障碍、管控功能障碍、知觉障碍(认识不能,或称失认症)或是行动障碍(运用不能,或称失用症)会比记忆障碍更明显[43]。阿兹海默症并非对病患的所有记忆能力都有相同影响,相对于新近发生的事情或记忆,病患人生的长期记忆(情节记忆)、语义记忆和内隐记忆(身体记住如何做一件事,例如使用叉子吃东西)受到的影响比较少[44][45]。

语言障碍(原发性进行性失语症)的主要特征是病患可使用的词汇变少,并且流畅度降低,因此导致病患的口语和书面语变得困难贫乏[43][46],在这一时期,病患通常能适当地表达简单的想法[43][46][47];当进行精细动作例如写作、画图、或是穿衣时,可能会出现一些动作不协调以及计划困难(动作缺陷症),但这些征兆通常会被忽略[43]。随着疾病进展,阿尔茨海默病患仍然能独立地完成许多事情,但是大部分需要认知功能的活动可能就需要协助或是监督[43]。

中期症状[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

随着病情渐渐恶化将导致病患失去独立性而无法进行大部分的日常生活活动[43]。由于无法想起词汇(命名不能症)使语言障碍变得明显,导致经常出现错误的字汇替换(言语错乱症),同时也渐渐失去读写能力[43][47],复杂的动作变得不协调,因此增加跌倒的风险[43],在这一时期,记忆问题会恶化,病患可能变得无法认得亲近的家属[43],之前仍完整的长期记忆也受到影响[43]。

此时期行为和神经精神病学的变化也更为显著,常见的表现是游荡(Wandering)、易怒(Irritability)和情感不稳,这些变化导致病患突然哭泣、突发的非故意攻击行为、或是拒绝接受照顾[43],此时也会出现日落症候群

晚期症状[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

在阿兹海默症的最终时期,病患已经完全依赖照护者[43],语言能力退化至简单的词语甚至仅有单字,最后完全失去谈话能力[43][47],除了失去口语能力之外,病患通常能理解及响应情感刺激[43],虽然攻击行为仍然存在,但极度冷漠和疲倦成为更常见的症状[43],最终病患会无法独立进行任何事务[43],肌肉质量和行动能力退化至长期卧床,也无法自行进食[43]。阿兹海默症是一种绝症,但是死因通常是外在因素,例如褥疮感染或是肺炎,而不是疾病本身[43]。

病理生理学[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

- 主条目:阿兹海默病病理生理学

神经病理学[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

阿兹海默症的特征是损失大脑皮质和一些皮质下区域的神经元和突触,损失神经元和突触导致受影响区域过多的萎缩,包括颞叶、顶叶、一部份的额叶和扣带皮层[48],学者利用磁振造影和正子计算机断层扫瞄纪录阿尔茨海默病患在疾病进展中的大脑影像,并与健康老年人的相同影像作比较,结果在大脑的特殊区域发现大脑质量退化[49][50]。

在显微镜下,阿尔茨海默病患大脑中的β淀粉样斑块和神经纤维缠结都清楚可见[51],蛋白质斑是高密度不溶于水的β类淀粉样蛋白质和细胞内容物在神经细胞周围堆积形成,神经纤维缠结则是由微管相关蛋白质Tau蛋白质过度磷酸化并且堆积在细胞内聚集而成,虽然许多老年人都会因为老化而在大脑出现蛋白质斑和神经纤维缠结,相比之下,阿尔茨海默病患在大脑中的特殊区域如颞叶有更多这些病变[52],路易体(Lewy body)在病患脑中也很常见[53]。

生物化学[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

阿兹海默症也被视为一种蛋白质折迭错误的疾病(蛋白质构象病),是由于大脑中折迭异常的β类淀粉蛋白质和Tau蛋白质堆积而造成[54]。老年瘢块是由长度约39—43个氨基酸名为模板:Le的小肽形成,β类淀粉蛋白质则是一个叫做前类淀粉蛋白质(APP)的较大蛋白质的片段,APP是一个穿过神经细胞膜的跨膜蛋白质,对于神经元的生长、存活和受伤后的修复非常重要 [55][56]。在阿兹海默症中,有个尚未厘清的机制导致APP被酵素切成几个较小的片段[57],其中一个片段使纤维和β类淀粉蛋白质增加,导致神经元外开始形成称为老年瘢块的团块堆积[51][58]。

还有一种理论认为阿兹海默症是Tau蛋白质异常沉积(Tauopathy)造成,每个神经元都有由微管组成的细胞内支撑系统,称为细胞骨架,这些微管的作用如同轨道,引导营养物质和其他分子在细胞本体和轴突之间来回移动。Tau蛋白质被磷酸化之后可以稳定微管,所以被归类为微管关连蛋白质。在阿尔茨海默病患中,Tau蛋白质发生了一些化学变化,变得过度磷酸化,接着就与其他蛋白质配对结合,产生神经纤维团块并且瓦解神经元的运输系统[59]。

疾病机转[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

目前仍不清楚β类淀粉蛋白质的异常合成与异常聚集如何导致阿兹海默症的病理变化[60],类淀粉蛋白质假说指出β类淀粉蛋白质是刺激神经元退化的主要角色,类淀粉蛋白质聚集成的纤维是有毒的蛋白质构造且会摧毁细胞的钙离子平衡,大量堆积类淀粉蛋白质纤维则会刺激细胞进行细胞凋亡[61],β类淀粉蛋白质也会选择性地在阿尔茨海默病灶处细胞的线粒体中堆积,并且抑制神经元使用葡萄糖,也会抑制许多酵素的功能[62]。

不同的发炎过程和细胞激素也可能在阿兹海默症的病理变化中扮演一定的角色,发炎是组织受伤的一般标记,也可能是免疫反应的标记[63]。

不同神经营养因子以及其受体的分布变化也在阿兹海默症中发现,例如脑源性神经营养因子[64][65]。

基因[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

虽然研究显示有些基因可能是阿兹海默症的危险因子,但是绝大部分的阿尔茨海默病患都不是因为遗传因素而患病,这些病患称为偶发型阿兹海默症;另一方面,约0.1%的病患具有体染色体显性家族性遗传变异,这些病患通常在65岁前发病,而被归类为家族型阿兹海默症[66]。

家族型阿尔茨海默病患大多可以归因于以下三个基因其中之一发生突变:前类淀粉蛋白质基因、Presenilin 1和Presenilin 2[67],而这些基因的突变会导致老年瘢块的主要成分β类淀粉蛋白质42在细胞中的产量升高[68],有些突变则不会增加β类淀粉蛋白质42在细胞中的产量,仅是改变细胞内β类淀粉蛋白质42和其他主要同型异构物(如β类淀粉蛋白质40)的比例[69][70]。这解释了为何某些Presenilin基因突变即使降低β类淀粉蛋白质产量仍可以导致疾病发生,也指出Presenilin蛋白质可能有其他功能,例如改变APP的功能或是β类淀粉蛋白质以外的其他片段的功能。

大部分阿尔茨海默病患并没有体染色体遗传疾病,这些病患称为偶发型阿兹海默症。然而还是有些基因的异常可能是罹患阿兹海默症的危险因子。最著名的基因危险因子是载脂蛋白E的ε4 对偶基因(APOEε4)[71][72],约有40% - 80%阿尔茨海默病患带有至少一个APOEε4对偶基因[72],其中异型合子个体罹患阿兹海默症的风险增加3倍,而同型合子个体中则增加15倍[66]。然而,这些基因造成的影响并非绝对是基因相关的。举例来说,有些尼日利亚人罹患阿兹海默症的风险与是否带有APOEε4对偶基因没有相关[73][74]。虽然基因学家同意其他许多基因也是阿兹海默症的危险因子,或是具有影响迟发型阿尔茨海默病情发展的保护效果[67],然而根据尼日利亚研究和尚未完成的阿兹海默症相关基因危险因子外显度的研究结果,均显示环境因素扮演更重要的角色。超过400个基因已被研究其与迟发偶发型阿兹海默症的关联,然而大部分的基因都没有发现明显相关性[66]。

有些研究发现TREM2基因突变会增加罹患阿兹海默症的风险达3到5倍[75][76],可能的原因是当TREM2基因突变时,脑中的白血球就无法控制大脑中β类淀粉蛋白质的产生量。

病理[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

阿兹海默病主要是神经细胞的损失(或退化),以及脑中出现类淀粉斑以及神经纤维纠结。已知遗传因素很重要。并且发现有三种不同体染色体显性基因与少数家族性、早发性AD有关。这三种分别是:Presenilin 1, Presenilin 2, Amyloid Precursor Protein。晚发性AD(LOAD)只找到一个易感性基因:the epsilon 4 allele of the APOE gene。发病的年纪有50%的遗传性。

在病理学上显示出脑组织萎缩、大脑皮质出现老年斑等现象。研究发现老年斑是β淀粉样蛋白的沉积所造成。从髓液将脑内β淀粉样蛋白进行定量控制的工具现在正在实用化研发阶段。

但是β淀粉样蛋白是否为本症的直接原因,或者是患病后呈现出的结果,现在还没有定论[26]。

病因[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

大部分病患罹患阿兹海默症的原因仍然不明[77][78](除了1%到5%的病患可以找到基因差异),目前有几个不同的假说试着解释阿兹海默症的病因:

胆碱性假说(Cholinergic hypothesis)[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

胆碱性假说是最早被提出来的假说,也是现今大部分阿兹海默症药物所依据的理论基础[79],该假说认为阿兹海默症是由于神经系统减少产生神经传导物质乙酰胆碱而造成的,虽然胆碱性假说的历史悠久,但是没有受到广泛的支持,主要是由于使用药物治疗乙酰胆碱缺乏后,对于阿兹海默症的疗效有限。其他胆碱性效应也曾被提出,例如:大量的类淀粉蛋白为沉淀导致广泛的神经发炎反应[48][80]。

类淀粉蛋白质假说(Amyloid hypothesis)[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

1991年,学者提出类淀粉蛋白质假说,认为β类淀粉蛋白质(βA)在大脑堆积可能是导致阿兹海默症的根本原因[81][82],根据研究发现前类淀粉蛋白质基因(APP)位在第21对染色体上,而唐氏综合症病患都多了一套第21对染色体基因,同时唐氏症病患几乎全都在40岁左右时罹患阿兹海默症[83][84],加上阿兹海默症的主要遗传危险因子E型载脂蛋白质会导致类淀粉蛋白质在大脑中累积[85],因此推测β类淀粉蛋白质是导致阿兹海默症的原因,进一步的证据则是来自于转殖基因老鼠实验,研究人员在实验老鼠身上表现突变型人类APP基因,结果发现实验老鼠的大脑会产生纤维状类淀粉蛋白质斑(fibrillar amyloid plaques)和类似阿兹海默症的大脑病理变化及空间学习障碍(spatial learning deficits)[86][87][88][89][90]。

然而在早期人体试验中曾发现一个实验性的疫苗可以清除类淀粉蛋白质斑,利用这个疫苗治疗失智症病患却没有显著的效果[91],因此研究者改而怀疑非蛋白质斑的β类淀粉蛋白质寡聚合物是其主要的致病型蛋白质,这些有毒的寡聚合物也被称为类淀粉蛋白质衍生可溶性配体(amyloid-derived diffusible ligands, ADDLs),这些配体会结合到神经细胞表面的受体并且改变神经突触的结构,因此破坏神经元沟通[92],由于其中一种β类淀粉蛋白质寡聚合物受体可能是普恩蛋白质,也就是引起狂牛症和库贾氏症的蛋白质,因此这些神经退化性疾病的机转可能与阿兹海默症有关[93]。

2009年,这个假说根据新的研究成果做了更新,认为另一个β类淀粉蛋白质的相关蛋白质可能才是阿兹海默症的主要罪魁祸首,新的研究显示在生命早年大脑快速生长时的一个与类淀粉蛋白质相关的修剪神经连结机制,可能会被老年时的老化过程刺激活化,这个机制活化之后则导致阿尔茨海默病患的神经枯萎[94]。N-APP这个APP胺基端的片段和β类淀粉蛋白质很靠近并且被一个相同的酵素从APP上切下来,N-APP与神经受体死亡受体6结合后刺激了自我摧毁的路径[94],DR6在人类大脑中易受阿兹海默症影响的区域有大量表现,所以很有可能N-APP/DR6路径在老年人的大脑中被骇而造成大脑损伤,在这个模型中,β类淀粉蛋白质扮演了辅助的角色,即是抑制了神经突触的功能。

微管相关蛋白质假说(Tau hypothesis)[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

微管相关蛋白质假说认为微管相关蛋白质异常是引起阿尔茨海默病情发展的主因[82],在这个模型中,过度磷酸化的Tau蛋白质开始与其他Tau蛋白质配对结合,结果在神经细胞中形成了神经纤维纠结[95],在这种情形下,神经细胞内的微小管开始瓦解并导致神经细胞内的运送系统崩坏[96],这将造成神经细胞之间的生化沟通失效,接着并导致神经细胞死亡[97]。

其他假说[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

单纯疱疹病毒第一型也被报导过在带有易感性apoE基因的人身上扮演引发阿兹海默症的角色[98]。

另一个假说认为阿兹海默症可能由大脑中与老化相关的髓磷脂断裂引起,这个假说并认为在髓磷脂断裂时释放出来的铁离子还可能会扩大伤害,维持体内平衡的髓磷脂修复过程则助长β类淀粉蛋白质和Tau蛋白质在大脑中囤积[99][100][101]。

氧化压力和生物金属失去体内平衡也可能是阿尔茨海默病患产生病理变化的重要因子[102][103]。

阿尔茨海默病患损失了70%负责产生正肾上腺素的蓝斑核细胞, 在新皮质和海马回,正肾上腺素除了是神经传导物质以外,在静脉曲张处扩散也可以作为神经细胞、神经胶质细胞和血管周围微环境的内源性抗发炎物[104],已有研究显示正肾上腺素会刺激老鼠小神经胶质细胞,进而抑制小神经胶质细胞产生细胞激素和及吞噬β类淀粉蛋白质,由这些发现推测蓝斑核退化可能是阿尔茨海默病患大脑中β类淀粉蛋白质产生囤积的原因[104]。

患病因素[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

阿兹海默病受遗传因素的一定影响。根据调査显示,80歳以后15%的人有罹患痴呆性疾患的危险。亲族中有阿兹海默病患者的场合患病的机率也相对要高。其中,更有13岁的年轻小女孩罹患阿兹海默症的纪录。 [105]

大规模调査显示多摄取蔬菜、鱼虾类食物将减少患阿兹海默病的机率、肉类的过多摄取则会使得机率提高。

蓝藻生物皆含有神经毒素β-甲氨基-L-丙氨酸,β-甲氨基-L-丙氨酸已经被证实会对动物产生强烈的毒性,加速动物脑神经退化、四肢肌肉萎缩等等,小量BMAA积累已能选择性杀死从老鼠的神经元。蓝藻门的生物包括发菜、螺旋藻等等。香港中文大学呼吁大众停止食用发菜,减轻患上阿兹海默症的风险。[106]

另外曾有抽烟摄取尼古丁能减少阿兹海默病的发病机率之说,但在大规模的研究后现在这一说法被否定[26]。

铝致病说[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

曾有学说认为摄取过量铝离子是阿兹海默病原因之一,但是这一说法目前已不被相信[107]。

阿兹海默病患者脑内检测出的铝离子浓度比正常人通常高出数十倍,这是阿兹海默病的成因还是导致的结果目前还不明。

此说源于第二次世界大战后关岛驻扎的美军患有老年痴呆的机率异常之高,经过调查后发现关岛地下水中铝离子的含量非常高,通过改为饮用雨水以及从其它岛屿提供的水后患病率马上急剧下降,由此得出铝致病说。另外日本纪伊半岛地区阿兹海默病患病比率极高,其地下水中铝离子含量也极高,通过完善用水设备后患病率下降也是这一学说的根据。

根据牛津大学神经病理学院三名教授的联合研究报告,已更正铝有害脑部之说法。这项研究对八十名老人痴呆症患者脑组织中作切片检查,证实铝并未存于病患脑中。以往认定铝元素与老人痴呆症有关,是因传统制作脑切片及染色过程中,铝元素常是必须用品,所以检查结果有铝元素,而牛津大学教授所使用的核子电镜,却是不须经过染色步骤即可进行分析切片。原来认为血液到脑部时通过血脑屏障时铝离子无法到达大脑,如今发现这种看法是错误的。[108]

治疗[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

目前没有治愈阿尔茨海默氏病的方法,现有的治疗本质上仍然是治标不治本,它提供了相对比较小的症状改善的好处。目前的治疗可分为药物、心理和护理。

药物疗法[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

五种药物是目前用于治疗阿尔茨海默氏病的认知问题:其中四种是乙酰胆碱酯酶抑制剂(他克林,tacrine、利凡斯的明,rivastigmine、加兰他敏,galantamine和多奈哌齐,donepezil)以及其他(美金刚,memantine)则是N-甲基-D-天门冬胺酸受体(NMDA受体)拮抗剂。

目前使用这些药物的效果大多还不理想。

乙酰胆碱酶(Acetylcholinesterase)抑制剂[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

2006年美国食品和药物管理局批准多奈哌齐({Donepezil,爱忆欣)用于治疗轻度、中度和重度的阿尔茨海默氏痴呆症。

研究表明胆碱酯酶阻断剂可减轻阿兹海默病患者的精神症状。日本Eisai株式会社研发的乙酰胆碱分解酵素阻断剂,作为认知改善药物被用于治疗阿兹海默病。

此外针对阿兹海默病伴有的失眠、易怒、幻觉、妄想等「周边症状」,通常投与适宜対症的药剂如安眠药、抗精神病药物、抗癫痫药物、抗抑郁症药物等。

NMDA受体拮抗剂[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

这类药物目前仅有 memantine 一种,许可适应症为中重度、及重度阿兹海默症。

神经元保护剂[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

神经元保护剂可以阻断谷氨酸的兴奋毒性(excitotoxicity),藉此减缓生活技能的日渐丧失,也是目前唯一治疗中、重度失智症的药物。

成纤维细胞修复因子(bFGF)[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

有报道称bFGF对人诱导的痴呆老鼠模型有一定的治疗作用,但没有临床报告。

其他的治疗法[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

通过散步等改善昼夜生活节奏,将有纪念意义的照片纪念品等放置在病人旁边给予安心感等药物以外的手段也被认为对患者的失眠、不安等症状有效。

相关疾病[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

注释[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

参考数据[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

- ^ 引用错误:

<ref>标签无效;未给name(名称)为Mend2012的ref(参考)提供文本 - ^ 引用错误:

<ref>标签无效;未给name(名称)为WHO2017的ref(参考)提供文本 - ^ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 Burns, A; Iliffe, S (5 February 2009). "Alzheimer's disease". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 338: b158. PMID 19196745.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Querfurth, HW; LaFerla, FM (28 January 2010). "Alzheimer's disease". The New England journal of medicine. 362 (4): 329–44. PMID 20107219.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Dementia Fact sheet N°362". who.int. April 2012. Archived from the original on 18 三月 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Beyond Memory Loss, Behavior Changes Are Often First Signs of Dementia.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Waldemar G; Dubois B; Emre M; et al. (January 2007). "Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer's disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline". Eur J eurol (in English). 14 (1): e1–e26. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01605.x. PMID 17222085.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ 8.0 8.1 Tabert MH, Liu X, Doty RL, Serby M, Zamora D, Pelton GH, arder K, Albers MW, Stern Y, Devanand DP (2005). "A 10-item smell identification cale related to risk for Alzheimer's disease". Ann. Neurol. (in English). 58 (1): 155–160. doi:10.1002/ana.20533. PMID 15984022.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "About Alzheimer's Disease: Symptoms". National Institute on Aging. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Mölsä PK, Marttila RJ, Rinne UK (March 1995). "Long-term survival and predictors of mortality in Alzheimer's disease and multi-infarct dementia". ActaNeurol Scand (in English). 91 (3): 159–64. PMID 7793228.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Ballard, C; Gauthier, S; Corbett, A; Brayne, C; Aarsland, D; Jones, E (19 March 2011). "Alzheimer's disease". Lancet. 377 (9770): 1019–31. PMID 21371747.

- ^ 杨雨哲, 孙承洲 (2014-09-30). "阿兹海默症的成因及治疗". 30 (3). ISSN 2220-6493. Archived from the original on 2015-01-23. Retrieved 2015-01-23.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mänz C, Reimold M, Bender B, Bares R, Ernemann U, Horger M (December 2012). "Bildgebende Diagnostik der Alzheimer-Krankheit". Fortschr Röntgenstr (in Deutsch). 184 (12): 1079–1082. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1319030.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Alzheimer's diagnosis of AD". Alzheimer's esearch Trust. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ "Dementia diagnosis and assessment" (PDF). pathways.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Klein C, Hagenah J, Landwehrmeyer B, Münte T, Klockgether T (August 2011). "Das präsymptomatische Stadium neurodegenerativer Erkrankungen". Nervenarzt (in Deutsch). 82 (8): 994–1001. doi:10.1007/s00115-011-3258-y.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Todd, S; Barr, S; Roberts, M; Passmore, AP (November 2013). "Survival in dementia and predictors of mortality: a review". International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 28 (11): 1109–24. PMID 23526458.

- ^ Zieschang T, Hauer K, Schwenk M (August 2012). "Körperliches Training bei Menschen mit Demenz". Dtsch med Wochenschr (in Deutsch). 137 (31/32): 1552–1555. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1305114.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "More research needed on ways to prevent Alzheimer's, panel finds". National Institute on Aging. 29 August 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 一月 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Clinical Trials. Found 1012 studies with search of: alzheimer". US National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ^ 模板:Vcite journal

- ^ Forbes, D.; Thiessen, E.J.; Blake, C.M.; Forbes, S.C.; Forbes, S. (4 December 2013). "Exercise programs for people with dementia". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 12: CD006489. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006489.pub3. PMID 24302466.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. "Low-dose antipsychotics in people with dementia". nice.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 十二月 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Information for Healthcare Professionals: Conventional Antipsychotics". fda.gov. 2008-06-16. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ 模板:Vcite journal

- ^ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "阿兹海默症的简介". 活力药师网. 2007-05-31. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ^ Mendez, MF (November 2012). "Early-onset Alzheimer's disease: nonamnestic subtypes and type 2 AD". Archives of medical research. 43 (8): 677–85. PMID 23178565.

- ^ Lozano, R; Naghavi, M; Foreman, K (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. PMID 23245604.

- ^ 模板:Vcite journal

- ^ 模板:Vcite journal

- ^ 模板:Vcite journal

- ^ 模板:Vcite journal

- ^ Dementia: Quick Reference Guide (PDF) (in English). London: (UK) National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2006. ISBN 1-84629-312-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 二月 2008. Retrieved 2014-04-20.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Schroeter ML, Stein T, Maslowski N, Neumann J (2009). "Neural Correlates of Alzheimer's Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic and Quantitative Meta-Analysis involving 1,351 Patients". NeuroImage. 47 (4): 1196–1206. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.037. PMC 2730171. PMID 19463961.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 模板:Vcite journal

- ^ 阿兹海默氏症的检查,2008年9月27日查阅

- ^ Alzheimer A (Jan 1907). "Über eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde". Allg. Z. Psychiat. Psych.-Gerichtl. Med. (in Deutsch). 64 (1–2): 146–148.

- ^ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Bäckman L, Jones S, Berger AK, Laukka EJ, Small BJ (Sep 2004). "Multiple cognitive deficits during the transition to Alzheimer's disease". J Intern Med (in English). 256 (3): 195–204. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01386.x. PMID 15324363.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nygård L 刀 (2003). "Instrumental activities of daily living: a stepping-stone towards Alzheimer's disease diagnosis in subjects with mild cognitive impairment?". Acta Neurol Scand (in English). Suppl (179): 42–6. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0404.107.s179.8.x. PMID 12603250.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Arnáiz E, Almkvist O (2003). "Neuropsychological features of mild cognitive impairment and preclinical Alzheimer's disease". Acta Neurol. Scand., Suppl. (in English). 179: 34–41. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0404.107.s179.7.x. PMID 12603249.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME, Geldmacher DS (Dec 2001). "Apathy in Alzheimer's disease". J Am Geriatr Soc (in English). 49 (12): 1700–7. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49282.x. PMID 11844006.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Petersen RC (February 2007). "The current status of mild cognitive impairment—what do we tell our patients?". Nat Clin Pract Neurol (in English). 3 (2): 60–1. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0402. PMID 17279076.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ 43.00 43.01 43.02 43.03 43.04 43.05 43.06 43.07 43.08 43.09 43.10 43.11 43.12 43.13 43.14 43.15 43.16 43.17 Förstl H, Kurz A (1999). "Clinical features of Alzheimer's disease". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (in English). 249 (6): 288–290. doi:10.1007/s004060050101. PMID 10653284.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Carlesimo GA, Oscar-Berman M (June 1992). "Memory deficits in Alzheimer's patients: a comprehensive review". Neuropsychol Rev (in English). 3 (2): 119–69. doi:10.1007/BF01108841. PMID 1300219.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Jelicic M, Bonebakker AE, Bonke B (1995). "Implicit memory performance of patients with Alzheimer's disease: a brief review". International Psychogeriatrics (in English). 7 (3): 385–392. doi:10.1017/S1041610295002134. PMID 8821346.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 46.0 46.1 Taler V, Phillips NA (July 2008). "Language performance in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a comparative review". J Clin Exp Neuropsychol (in English). 30 (5): 501–56. doi:10.1080/13803390701550128. PMID 18569251.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Frank EM (September 1994). "Effect of Alzheimer's disease on communication function". J S C Med Assoc (in English). 90 (9): 417–23. PMID 7967534.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ 48.0 48.1 Wenk GL (2003). "Neuropathologic changes in Alzheimer's disease". J Clin Psychiatry (in English). 64 Suppl 9: 7–10. PMID 12934968.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Desikan RS (August 2009). "Automated MRI measures identify individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease". Brain (in English). 132 (8): 2048–57. doi:10.1093/brain/awp123. PMC 2714061. PMID 19460794.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Moan R (2009-07-20). "MRI software accurately IDs preclinical Alzheimer's disease" (in English). Diagnostic Imaging. Retrieved 2013-01-07.

- ^ 51.0 51.1 Tiraboschi P, Hansen LA, Thal LJ, Corey-Bloom J (June 2004). "The importance of neuritic plaques and tangles to the development and evolution of AD". Neurology (in English). 62 (11): 1984–9. PMID 15184601.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bouras C, Hof PR, Giannakopoulos P, Michel JP, Morrison JH (1994). "Regional distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in the cerebral cortex of elderly patients: a quantitative evaluation of a one-year autopsy population from a geriatric hospital". Cereb. Cortex (in English). 4 (2): 138–50. doi:10.1093/cercor/4.2.138. PMID 8038565.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kotzbauer PT, Trojanowsk JQ, Lee VM (Oct 2001). "Lewy body pathology in Alzheimer's disease". J Mol Neurosci (in English). 17 (2): 225–32. doi:10.1385/JMN:17:2:225. PMID 11816795.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hashimoto M, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Masliah E (2003). "Role of protein aggregation in mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases". Neuromolecular Med. (in English). 4 (1–2): 21–36. doi:10.1385/NMM:4:1-2:21. PMID 14528050.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Priller C, Bauer T, Mitteregger G, Krebs B, Kretzschmar HA, Herms J (July 2006). "Synapse formation and function is modulated by the amyloid precursor protein". J. Neurosci. (in English). 26 (27): 7212–21. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1450-06.2006. PMID 16822978.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Turner PR, O'Connor K, Tate WP, Abraham WC (May 2003). "Roles of amyloid precursor protein and its fragments in regulating neural activity, plasticity and memory". Prog. Neurobiol. (in English). 70 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1016/S0301-0082(03)00089-3. PMID 12927332.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hooper NM (April 2005). "Roles of proteolysis and lipid rafts in the processing of the amyloid precursor protein and prion protein". Biochem. Soc. Trans. (in English). 33 (Pt 2): 335–8. doi:10.1042/BST0330335. PMID 15787600.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Ohnishi S, Takano K (March 2004). "Amyloid fibrils from the viewpoint of protein folding". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. (in English). 61 (5): 511–24. doi:10.1007/s00018-003-3264-8. PMID 15004691.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Hernández F, Avila J (September 2007). "Tauopathies". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. (in English). 64 (17): 2219–33. doi:10.1007/s00018-007-7220-x. PMID 17604998.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Van Broeck B, Van Broeckhoven C, Kumar-Singh S (2007). "Current insights into molecular mechanisms of Alzheimer disease and their implications for therapeutic approaches". Neurodegener Dis (in English). 4 (5): 349–65. doi:10.1159/000105156. PMID 17622778.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yankner BA, Duffy LK, Kirschner DA (October 1990). "Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid beta protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides". Science (in English). 250 (4978): 279–82. doi:10.1126/science.2218531. PMID 2218531.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chen X, Yan SD (December 2006). "Mitochondrial Abeta: a potential cause of metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease". IUBMB Life (in English). 58 (12): 686–94. doi:10.1080/15216540601047767. PMID 17424907.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Greig NH; Mattson MP; Perry T; et al. (December 2004). "New therapeutic strategies and drug candidates for neurodegenerative diseases: p53 and TNF-alpha inhibitors, and GLP-1 receptor agonists". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. (in English). 1035: 290–315. doi:10.1196/annals.1332.018. PMID 15681814.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Tapia-Arancibia L, Aliaga E, Silhol M, Arancibia S (Nov 2008). "New insights into brain BDNF function in normal aging and Alzheimer disease". Brain Research Reviews (in English). 59 (1): 201–20. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.07.007. PMID 18708092.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schindowski K, Belarbi K, Buée L (Feb 2008). "Neurotrophic factors in Alzheimer's disease: role of axonal transport". Genes, Brain and Behavior (in English). 7 (Suppl 1): 43–56. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00378.x. PMC 2228393. PMID 18184369.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 66.0 66.1 66.2 Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H (July 2006). "Alzheimer's disease". Lancet (in English). 368 (9533): 387–403. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. PMID 16876668.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 67.0 67.1 Waring SC, Rosenberg RN (March 2008). "Genome-wide association studies in Alzheimer disease". Arch Neurol (in English). 65 (3): 329–34. doi:10.1001/archneur.65.3.329. PMID 18332245.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Selkoe DJ (June 1999). "Translating cell biology into therapeutic advances in Alzheimer's disease". Nature (in English). 399 (6738 Suppl): A23–31. doi:10.1038/19866. PMID 10392577.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Borchelt DR; Thinakaran G; Eckman CB; et al. (Nov 1996). "Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate βA1-42/1-40 ratio in vitro and in vivo". Neuron (Original article) (in English). 17 (5): 1005–13. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80230-5. PMID 8938131.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Shioi J; Georgakopoulos A; Mehta P; et al. (May 2007). "FAD mutants unable to increase neurotoxic Aβ 42 suggest that mutation effects on neurodegeneration may be independent of effects on Abeta". J Neurochem (in English). 101 (3): 674–81. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04391.x. PMID 17254019.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Strittmatter WJ; Saunders AM; Schmechel D; et al. (March 1993). "Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (in English). 90 (5): 1977–81. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977. PMC 46003. PMID 8446617.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ 72.0 72.1 Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y (April 2006). "Apolipoprotein E4: A causative factor and therapeutic target in neuropathology, including Alzheimer's disease". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. (in English). 103 (15): 5644–51. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600549103. PMC 1414631. PMID 16567625.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hall K, Murrell J, Ogunniyi A, Deeg M, Baiyewu O, Gao S, Gureje O, Dickens J, Evans R, Smith-Gamble V, Unverzagt FW, Shen J, Hendrie H (January 2006). "Cholesterol, APOE genotype, and Alzheimer disease: an epidemiologic study of Nigerian Yoruba". Neurology. 66 (2): 223–227. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000194507.39504.17. PMC 2860622. PMID 16434658.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gureje O, Ogunniyi A, Baiyewu O, Price B, Unverzagt FW, Evans RM, Smith-Gamble V, Lane KA, Gao S, Hall KS, Hendrie HC, Murrell JR (January 2006). "APOE ε4 is not associated with Alzheimer's disease in elderly Nigerians". Ann Neurol. 59 (1): 182–185. doi:10.1002/ana.20694. PMC 2855121. PMID 16278853.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jonsson, Thorlakur; Stefansson, Hreinn; Steinberg, Stacy; Jonsdottir, Ingileif; Jonsson, Palmi V; Snaedal, Jon; Bjornsson, Sigurbjorn; Huttenlocher, Johanna; Levey, Allan I (2012). "Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer's disease". New England Journal of Medicine (Original article) (in English). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1211103.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Guerreiro, Rita; Wojtas, Aleksandra; Bras, Jose; Carrasquillo, Minerva; Rogaeva, Ekaterina; Majounie, Elisa; Cruchaga, Carlos; Sassi, Celeste; Kauwe, John S.K. (2012). "TREM2 variants in Alzheimer's disease". New England Journal of Medicine (Original article) (in English). doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1211851.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^

"What We Know Today About Alzheimer's Disease". Alzheimer's Association. Retrieved 2012-12-20.

While scientists know Alzheimer's disease involves progressive brain cell failure, the reason cells fail isn't clear.

- ^ "Alzheimer's Disease: Causes". NYU Medical Center/NYU School of Medicine. Retrieved 2012-12-20.

The cause of Alzheimer's disease is not yet known, but scientists are hoping to find the answers by studying the characteristic brain changes that occur in a patient with Alzheimer's disease. In rare cases when the disease emerges before the age of sixty-five, these brain changes are caused by a genetic abnormality. Scientists are also looking to genetics as well as environmental factors for possible clues to the cause and cure of Alzheimer's disease.

- ^ Francis PT, Palmer AM, Snape M, Wilcock GK (February 1999). "The cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: a review of progress". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. (in English). 66 (2): 137–47. doi:10.1136/jnnp.66.2.137. PMC 1736202. PMID 10071091.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shen ZX (2004). "Brain cholinesterases: II. The molecular and cellular basis of Alzheimer's disease". Med Hypotheses (in English). 63 (2): 308–21. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2004.02.031. PMID 15236795.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Hardy J, Allsop D (October 1991). "Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. (in English). 12 (10): 383–88. doi:10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-V. PMID 1763432.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ 82.0 82.1 Mudher A, Lovestone S (January 2002). "Alzheimer's disease-do tauists and baptists finally shake hands?". Trends Neurosci. (in English). 25 (1): 22–26. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(00)02031-2. PMID 11801334.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Nistor M; Don M; Parekh M; et al. (October 2007). "Alpha- and beta-secretase activity as a function of age and beta-amyloid in Down syndrome and normal brain". Neurobiol Aging (in English). 28 (10): 1493–1506. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.023. PMID 16904243.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Lott IT, Head E (March 2005). "Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome: factors in pathogenesis". Neurobiol Aging (in English). 26 (3): 383–89. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.08.005. PMID 15639317.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Polvikoski T; Sulkava R; Haltia M; et al. (November 1995). "Apolipoprotein E, dementia, and cortical deposition of beta-amyloid protein". N Engl J Med (in English). 333 (19): 1242–47. doi:10.1056/NEJM199511093331902. PMID 7566000.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Howlett DR (December 2011). "APP transgenic mice and their application to drug discovery". Histol Histopathol (in English). 26 (12): 1611–1632.

- ^ Games D; Adams D; Alessandrini R; et al. (February 1995). "Alzheimer-type neuropathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F beta-amyloid precursor protein". Nature (in English). 373 (6514): 523–27. doi:10.1038/373523a0. PMID 7845465.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Masliah E, Sisk A, Mallory M, Mucke L, Schenk D, Games D (September 1996). "Comparison of neurodegenerative pathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F beta-amyloid precursor protein and Alzheimer's disease". J Neurosci (in English). 16 (18): 5795–811. PMID 8795633.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hsiao K; Chapman P; Nilsen S; et al. (October 1996). "Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice". Science (in English). 274 (5284): 99–102. doi:10.1126/science.274.5284.99. PMID 8810256.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Lalonde R, Dumont M, Staufenbiel M, Sturchler-Pierrat C, Strazielle C. (2002). "Spatial learning, exploration, anxiety, and motor coordination in female APP23 transgenic mice with the Swedish mutation". Brain Research (journal) (in English). 956 (1): 36–44. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03476-5. PMID 12426044.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Holmes C; Boche D; Wilkinson D; et al. (July 2008). "Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer's disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial". Lancet (in English). 372 (9634): 216–23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2. PMID 18640458.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Lacor PN; et al. (January 2007). "Aß Oligomer-Induced Aberrations in Synapse Composition, Shape, and Density Provide a Molecular Basis for Loss of Connectivity in Alzheimer's Disease". Journal of Neuroscience (in English). 27 (4): 796–807. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-06.2007. PMID 17251419.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Lauren J; Gimbel D; et al. (February 2009). "Cellular Prion Protein Mediates Impairment of Synaptic Plasticity by Amyloid-β Oligomers". Nature (in English). 457 (7233): 1128–32. doi:10.1038/nature07761. PMC 2748841. PMID 19242475.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ 94.0 94.1 Nikolaev A, McLaughlin T, O'Leary D, Tessier-Lavigne M (19 February 2009). "APP binds DR6 to cause axon pruning and neuron death via distinct caspases". Nature (in English). 457 (7232): 981–989. doi:10.1038/nature07767. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 2677572. PMID 19225519.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Crowther RA (July 1991). "Tau proteins and neurofibrillary degeneration". Brain Pathol (in English). 1 (4): 279–86. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1991.tb00671.x. PMID 1669718.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Iqbal K; Alonso Adel C; Chen S; et al. (January 2005). "Tau pathology in Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies". Biochim Biophys Acta (in English). 1739 (2–3): 198–210. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.09.008. PMID 15615638.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Chun W, Johnson GV (2007). "The role of tau phosphorylation and cleavage in neuronal cell death". Front Biosci (in English). 12: 733–56. doi:10.2741/2097. PMID 17127334.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Itzhaki RF, Wozniak MA (May 2008). "Herpes simplex virus type 1 in Alzheimer's disease: the enemy within". J Alzheimers Dis (in English). 13 (4): 393–405. ISSN 1387-2877. PMID 18487848. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ Bartzokis G (August 2011). "Alzheimer's disease as homeostatic responses to age-related myelin breakdown". Neurobiol. Aging (in English). 32 (8): 1341–71. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.08.007. PMC 3128664. PMID 19775776.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Mintz J (December 2004). "Quantifying age-related myelin breakdown with MRI: novel therapeutic targets for preventing cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease". J. Alzheimers Dis. (in English). 6 (6 Suppl): S53–9. PMID 15665415.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bartzokis G, Lu PH, Mintz J (April 2007). "Human brain myelination and beta-amyloid deposition in Alzheimer's disease". Alzheimers Dement (in English). 3 (2): 122–5. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2007.01.019. PMC 2442864. PMID 18596894.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Su B, Wang X, Nunomura A; et al. (December 2008). "Oxidative stress signaling in Alzheimer's disease". Curr Alzheimer Res (in English). 5 (6): 525–32. doi:10.2174/156720508786898451. PMC 2780015. PMID 19075578.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kastenholz B, Garfin DE, Horst J, Nagel KA (2009). "Plant metal chaperones: a novel perspective in dementia therapy". Amyloid (in English). 16 (2): 81–3. doi:10.1080/13506120902879392. PMID 20536399.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 104.0 104.1 Heneka, MT (2010). "Locus ceruleus controls Alzheimer's disease pathology by modulating microglial functions through norepinephrine" (PDF). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (in English). 107: 6058–6063. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909586107. PMID 20231476. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ 英国13岁女童患老人痴呆症

- ^ Greg Miller. Guam's Deadly Stalker: On the Loose Worldwide? Science July 2006, 28 (313), 428-431. [1]

- ^ http://alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=99

- ^ "Aluminium and Alzheimer's disease". Retrieved 2012-06-15.

- Huntley, J., Bor, D., Hampshire, A., Owen, A., & Howard, R. (2011). Working memory task performance and chunking in early alzheimer's disease. British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(5), 398-403

延伸阅读[编辑 | 编辑源代码]

- Alzheimer's Disease: Unraveling the Mystery. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Aging, NIH. 2008. Archived from the original on 2012-01-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Wolfgang Maier, Jörg B. Schulz, Sascha Weggen (2011). Alzheimer & Demenzen Verstehen: Diagnose, Behandlung, Alltag, Betreuung. Stuttgart: Trias. ISBN 978-3-8304-6441-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Can Alzheimer's Disease Be Prevented? (PDF). US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Aging, NIH. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-02.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Caring for a Person with Alzheimer's Disease: Your Easy-to-Use Guide from the National Institute on Aging. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Aging, NIH. 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-01-08.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - 模板:Vcite journal

- 模板:Vcite journal

- Russell D, Barston S, White M (2007-12-19). "Alzheimer's Behavior Management: Learn to Manage Common Behavior Problems". helpguide.org. Archived from the original on 23 二月 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)